Stand on Framwellgate Bridge and you’re standing on history itself. The stones beneath your feet, worn smooth by nine centuries of pilgrims, soldiers, and visitors, hold the story of Durham. Looking south, the incredible view of Durham Cathedral and Castle rises above the River Wear, a panorama that has inspired people for generations.

This isn’t just a bridge; it’s a living document. Its arches and foundations tell tales of Norman conquest, devastating floods, notorious crimes, and the evolution of a city. As the oldest of Durham’s great medieval bridges and a key part of its UNESCO World Heritage Site, understanding this structure is the key to understanding Durham itself.

A Tale of Two Bridges: The 900-Year History of a Crossing

This is one of the most visiting bridges in Durham. Its history is a cycle of construction, destruction, and rebuilding, each chapter reflecting the ambitions and challenges of its time. This 900-year framwellgate bridge story offers a unique timeline of Durham’s journey from a Norman stronghold to a modern heritage city.

The First Crossing: Bishop Flambard’s 12th Century Ambition (c. 1128)

The first permanent bridge here was a bold Norman project built around 1128 by the powerful Bishop Ranulf Flambard. A key figure in establishing Norman control in the north, Flambard understood that a stone bridge was a strategic necessity, replacing the risky fords or flimsy wooden structures of the past.

His bridge, likely with five or six stone arches, was a marvel of its time. It secured the main northern approach to the Durham peninsula, the seat of the Prince-Bishops’ power. It also funnelled trade and commerce from the ‘Old Borough’ of Framwellgate directly into the Bishop’s control, making it a powerful statement of Norman authority.

“Broken by a Flood”: The Great Flood of 1400

After standing for nearly 300 years, Flambard’s bridge met a dramatic end. Historical records confirm it was “broken by a flood” in 1400, a catastrophic event that destroyed the Norman structure and cut off the city’s essential northern connection.

The city’s response was immediate. A ferry service was quickly established to cross the river, a clear sign of the crossing’s importance. The profits were shared between the Bishop of Durham and the Prior of Durham Cathedral, showing the significant economic impact of the bridge’s loss.

Rebuilt in Stone: Bishop Langley’s 15th Century Masterpiece

Today’s Framwellgate Bridge Durham is the resilient structure that rose from the ruins of the first. Rebuilt in the early 15th century under Bishop Thomas Langley, it was designed to be stronger and more robust.

Its wide, powerful arches were engineered to better withstand the mighty currents of the River Wear that had destroyed its predecessor. This late-medieval masterpiece is the historic core of the bridge that visitors still walk across today.

Bridges in Durham for a New Age: 19th Century Widening

For 400 years, Bishop Langley’s bridge served its purpose well. But the Industrial Revolution brought new demands. Increased coal mining and the building of North Road in 1830 led to a surge in heavy traffic, turning the narrow medieval bridge into a major bottleneck.

To solve this, the bridge was widened on its upstream side in the early 19th century, nearly doubling its width. This practical change shows the exact moment when industrial needs overtook medieval design. The seam between the 15th-century core and the 19th-century addition is still clearly visible.

From Traffic Jam to Tourist Gem: 20th Century Pedestrianisation

The widening was only a temporary fix. Throughout the 20th century, the rise of motorised transport turned Framwellgate Bridge and the adjoining Silver Street into a famous traffic jam. Until the new Milburngate Bridge opened in 1969, double-decker buses and lorries squeezed over this ancient route.

The situation led to a manned police box being installed in the Market Place just to control the flow of traffic. The opening of Milburngate Bridge finally allowed for the full pedestrianisation of Framwellgate, transforming it from a congested artery into a treasured historical monument. This move preserved its structure, allowing it to be enjoyed as a centrepiece of the visitor experience. For those exploring the city today, a variety of taxi services make reaching this pedestrianised heart of Durham simple.

An Architectural Deep Dive: Reading the Story in the Stones

Framwellgate Bridge is an open-air architecture lesson. Its materials, design, and enduring mysteries reveal over 600 years of engineering, adaptation, and style. By looking closely, you can read the physical evidence of its long evolution.

Design and Materials: A Blend of Strength and Grace

The bridge is made of coursed squared sandstone with ashlar dressings, reflecting the high-quality craftsmanship available to the Prince-Bishops. The stones were cut into regular blocks and laid in strong horizontal rows, while the finer, smooth-faced ashlar stone was used for details like the outlines of the arches.

The two main arches are elliptical, a design more efficient and better at handling water flow than the semi-circular Norman style. This was a deliberate choice by Bishop Langley’s masons, a direct lesson learned from the flood of 1400. The central pier is shielded by a sharp triangular cutwater, designed to break the river’s current and protect the foundation.

The Seven Ribs: A Visible Timeline

One of the most incredible details is hidden on the underside of the bridge. Each arch is supported by seven square reinforcing ribs, a common medieval technique for adding strength.

On Framwellgate Bridge, these ribs tell a unique story. A close look reveals that five of the ribs are from Bishop Langley’s original 15th-century build, while two were added during the 19th-century widening. This visible difference allows you to physically trace the bridge’s history, a seam in time you can see and touch.

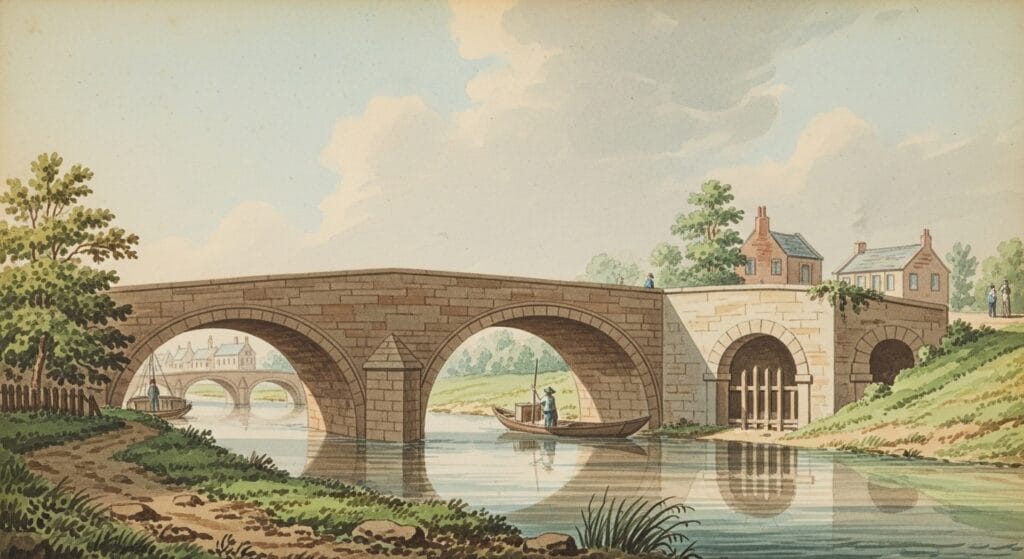

The Enduring Mystery of the Lost Third Arch

While two arches clearly cross the river today, historical evidence strongly suggests there was once a third. This “lost arch” is one of Durham’s most fascinating architectural puzzles.

The 16th-century writer John Leland first recorded three arches. More compellingly, a 1799 watercolour by Thomas Girtin clearly shows a third, rounded arch at the city-side end of the bridge. This has led to the theory that buildings on Silver Street now conceal this third arch. The rounded shape has even fueled speculation that it might be a surviving piece of Bishop Flambard’s original 12th-century Norman bridge. As no modern survey has found a trace of it, the mystery remains a hidden part of Durham’s story.

The Bridge as a Stage: Power, Murder, and Commerce

Framwellgate Bridge was never just infrastructure; it was the stage for medieval Durham’s daily drama. It was a symbol of power, the scene of a shocking crime, and a buzzing hub of commerce, central to the city’s defence and trade.

“Half Church, Half Castle”: A Fortified Gateway

In a city known as “Half church of God, half castle ‘gainst the Scot,” the main bridge was a key defensive point. Framwellgate Bridge served as the primary northern gateway to the fortified peninsula, home to the Castle and the magnificent Durham Cathedral.

It was heavily fortified with a gatehouse that controlled all traffic, acting as a checkpoint to tax goods and repel potential threats. The gatehouse was demolished in 1760 because it was an “obstruction to traffic,” a moment that symbolises the shift from medieval military concerns to the priorities of commerce.

Murder on the Bridge: The Peacock and the Steward (1318)

In 1318, the bridge was the scene of one of Durham’s most infamous murders. Robert Neville, a nobleman known as the “Peacock of the North,” killed his cousin, Sir Richard Fitzmarmaduke, right on the bridge.

Fitzmarmaduke was the Bishop’s Steward, the chief official of the Prince-Bishop. This public assassination was a brazen act of political defiance against the Bishop’s authority, sending shockwaves across the region.

A Medieval Marketplace: Tolls, Trade, and Commerce

Beyond defence, the bridge was a vital economic engine. In medieval times, tolls were collected on people and goods crossing the bridge, providing essential revenue for the Bishop.

The bridge itself would have been a crowded street, lined with shops and booths. As the main entrance to the city, it was a prime spot for merchants. Archaeological finds of lead cloth seals in the river nearby confirm a bustling textile trade flowed across this very bridge, connecting Durham to wider markets.

Durham’s Three Great Bridges: A Comparative View

Framwellgate is the oldest of a trio of historic bridges in the Durham peninsula, alongside Elvet Bridge and Prebends Bridge. Each was built in a different era for a different reason, and together they tell a complete story of the city’s development.

| Feature | Framwellgate Bridge | Elvet Bridge | Prebends Bridge |

| Date Built | Original c. 1128; Rebuilt post-1400 | c. 1160–1195 | 1772–1778 |

| Original Builder | Bishop Ranulf Flambard | Bishop Hugh de Puiset | George Nicholson (for Dean & Chapter) |

| Original Purpose | Main northern crossing; defense; commerce | Connect Elvet to Market Place; commerce | Private road for Dean & Chapter; aesthetic views |

| Key Feature | Oldest crossing; murder site; “lost arch” | Had two Chantry Chapels; housed a gaol | Built for the view of the Cathedral |

| Style | Medieval (Gothic/Norman) | Medieval | Georgian / Neoclassical |

| Current Status | Pedestrianised; Grade I Listed | Road traffic; Grade I Listed | Pedestrianised; Grade I Listed |

A Visitor’s and Photographer’s Guide to Framwellgate Bridge

Today, Framwellgate Bridge is a must-see for any visitor to Durham. Its rich history is matched by its stunning views and its role in the city’s best walks. It’s a key destination in many year-round guides to Durham’s events and attractions.

How to Get There & What’s Nearby

- Location: The bridge connects Silver Street (near the Market Place) with North Road. It is in the heart of the city centre.

- Transport: Durham Train Station and Bus Station are just a short walk down North Road. For a seamless journey from the station or one of the city’s excellent hotels, you can simplify your travel by booking a taxi in advance.

- Nearby Attractions: The bridge is your gateway to the Durham World Heritage Site. Durham Cathedral, Durham Castle, and Durham Market Hall are all within a five-minute walk.

The Perfect Shot: A Photographer’s Guide

- Best Vantage Points: The most famous photo of Durham is taken from the riverside path on the west bank, just south of the bridge. For a longer view, walk upstream to Prebends Bridge. Don’t forget the view from Framwellgate Bridge itself, looking towards the cathedral.

- Best Time of Day: The “golden hour” after sunrise bathes the Cathedral in warm light. The “blue hour” after sunset is perfect for capturing the bridge’s illuminated lamps against the twilight sky.

- Pro-Tips: Use a tripod for a long exposure to smooth the river’s water. Try a portrait orientation to capture the soaring height of the Cathedral. Autumn provides a stunning backdrop of colourful trees.

A Walk Through History: The Durham Riverside Circuit

The bridge is a key part of the popular Durham Riverside Walk. For a perfect loop that takes less than an hour:

- Start in the Market Place and walk down Silver Street to Framwellgate Bridge.

- Cross the bridge and turn left onto the riverside path. This section offers the classic postcard views.

- Follow the path south until you reach Prebends Bridge.

- Cross Prebends Bridge and turn left, following the wooded path below the Cathedral.

- The path leads back towards the city, passing under Elvet Bridge and returning you near the Market Place.

FAQ: Answering Your Questions About Framwellgate Bridge

How old is Framwellgate Bridge?

The current stone bridge is over 600 years old, dating to the early 15th century. It replaced an even older Norman bridge from around 1128 that was destroyed in a flood.

What is the story of the murder on the bridge?

In 1318, a powerful nobleman, Robert Neville (“The Peacock of the North”), murdered his cousin, Sir Richard Fitz Marmaduke, on the bridge. Fitz Marmaduke was the Bishop of Durham’s chief official, making the murder a major political crime.

What is the difference between Framwellgate, Elvet, and Prebends Bridge?

Framwellgate (c. 1128/1400s) is the oldest, built for defence and trade. Elvet (c. 1170) is the second oldest and once housed chapels and a prison. Prebends (1770s) is the youngest of the three and was built purely for its beautiful views of the Cathedral.

Can you drive over Framwellgate Bridge?

No. The bridge has been fully pedestrianised since 1969. It was once a major traffic route but is now a peaceful walkway for locals and tourists.

Why is Framwellgate Bridge famous?

It’s famous for being Durham’s oldest bridge, its central role in the city’s history, the infamous murder that occurred on it, the mystery of its “lost” third arch, and for offering one of the most iconic views of Durham Cathedral and Castle.